Summary: A statistical theory of rogue waves is proposed and

tested against experimental data collected in a long water tank

where random waves with different degrees of nonlinearity are

mechanically generated and free to propagate along the

flume. Strong evidence is given that the rogue waves observed in

the tank are hydrodynamic instantons, that is, saddle

point configurations of the action associated with the stochastic

model of the wave system. As shown here, these hydrodynamic

instantons are complex spatio-temporal wave field configurations

which can be defined using the mathematical framework of Large

Deviation Theory and calculated via tailored numerical

methods. These results indicate that the instantons describe

equally well rogue waves that originate from a simple linear

superposition mechanism (in weakly nonlinear conditions) or from a

nonlinear focusing one (in strongly nonlinear conditions), paving

the way for the development of a unified explanation to rogue wave

formation.

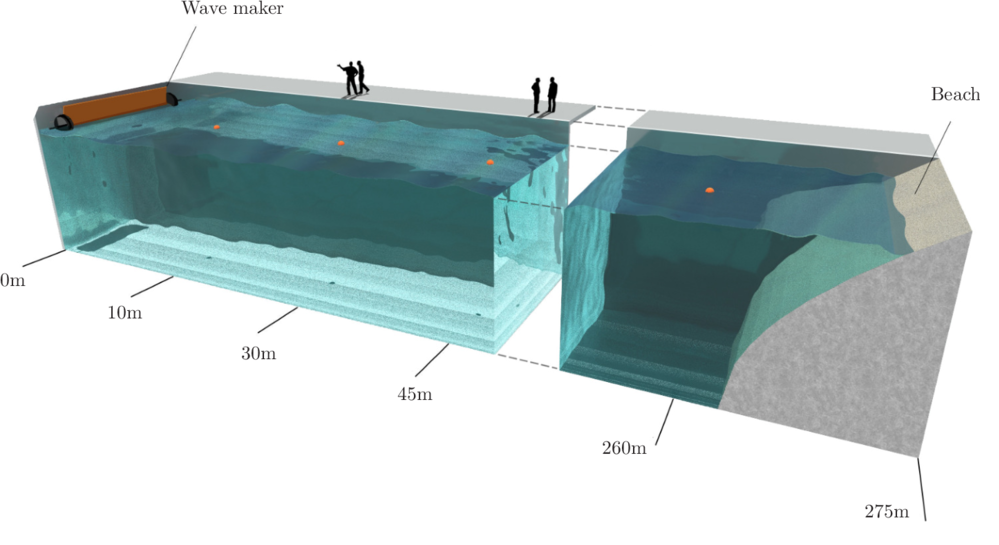

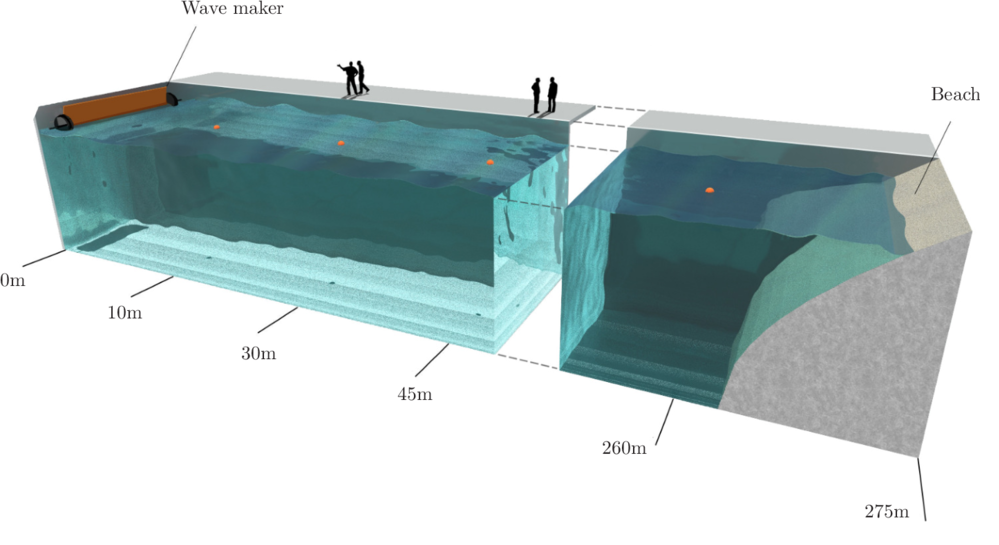

Experimental Setup

The experimental data were recorded in the 270m long wave flume at

Marintek (Norway), schematically represented in the schematic. At one

end of the tank a plane-wave generator perturbs the water surface with

a predefined random signal, here taken to be the JONSWAP spectrum,

modelling a random sea state, with enhancement factor

\(\gamma\). These perturbations create long-crested wave trains that

propagate along the tank toward the opposite end, where they

eventually break on a smooth beach that suppresses most of the

reflections. The water surface \(\eta(x,t)\) is measured by probes

placed at different distances from the wave maker (\(x\)-coordinate).

The signal at the wave maker \(\eta(x=0,t) \equiv \eta_0(t)\) is

prepared according to the stationary random-phase statistics with

deterministic spectral amplitudes \(C(\omega_j)\). Experimental data

were collected for three different regimes: quasi-linear

(\(\gamma=1\), \(H_s=0.11\) m), intermediate (\(\gamma=3.3\),

\(H_s=0.13\) m), and highly nonlinear (\(\gamma=6\), \(H_s=0.15\) m).

Note that these three regimes have comparable significant wave

heights \(H_s\), but the difference in their enhancement

factors \(\gamma\) has significant dynamical consequences.

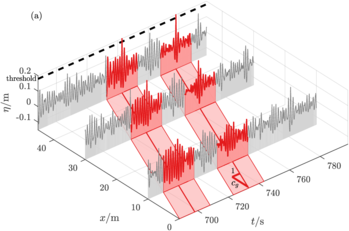

Extreme-event filtering: Extracting rogue waves from experimental data

To characterize the dynamics leading to extreme events of the water

surface, we adopt the following procedure: at a fixed location \(x=L\)

along the flume, we select small observation windows around all

temporal maxima of \(\eta\) that exceed a threshold \(z\). The choice of

the threshold \(z\) is meant to select extreme events with a similar

probability for all sets: the values of \(z=H_s=4\sigma\) for the

quasi-linear set, \(z=1.1\,H_s=4.4\sigma\) for the intermediate set and

\(z=1.2\,H_s=4.8\sigma\) for the highly-nonlinear set, where the maximum of the

surface elevation exceeds the threshold at the \(45\) m probe,

\(\eta(x=45\) m\(,t)\ge z\). We track the wave packet backward in space

and look at its shape at earlier points in the channel. This allows us

to build a collection of extreme events and monitor their

precursors.

Theoretical description of rogue waves via instantons of NLSE

To avoid solving fully nonlinear water wave equations that are

complicated from both theoretical and computational viewpoints, it is

customary to use simplified models such as the Nonlinear Schr\"odinger

equation (NLSE). If we exclude very nonlinear initial data, it is

known that NLSE captures the statistical properties of one dimensional

wave propagation to a good degree of accuracy up to a certain

time and it can be improved upon by using higher

order envelope equations. Because of their simplicity, NLSE and

extensions thereof have been successfully used to explain basics

mechanisms such as the modulational instability in water waves. With

the aim of capturing leading order effects, rather than describing the

full wave dynamics, here we restrict ourselves to the NLSE as a

prototype model for describing the nonlinear and dispersive waves in

the wave flume.

In the limit of deep-water, small-steepness, and

narrow-band properties, the evolution of the system is

described, to leading order in nonlinearity and dispersion, by the

one-dimensional NLSE:

$$

\frac{\partial \psi}{\partial x} + 2\frac{k_0}{\omega_0}

\frac{\partial \psi}{\partial t} + {i} \frac{k_0}{\omega_0^2}

\frac{\partial^2 \psi}{\partial t^2}+ 2 i {k_0^3} |\psi|^2\psi

= 0\,.

$$

The NLSE describes the change of the complex envelope \(\psi\equiv\psi(x,t)\)

that relates to the surface elevation via the Stokes series truncated

at second order:

$$

\eta = |\psi|\cos(\theta) + \tfrac12 k_0 |\psi|^2\cos(2\theta) +

O(k_0^2 |\psi|^3)\,,

$$

where \(\theta=k_0 x - \omega_0 t + \beta\) and \(\beta\) is the phase of

\(\psi\). In this expression the second order term can be neglected when

the field amplitude \(|\psi|\) is small — this is the case near the wave

maker at \(x=0\), where we will specify initial conditions for the

NLSE. However, this second order correction is

important when \(|\psi|\) becomes large, i.e. when rogue waves develop.

The NLSE is written as an evolution equation in space (rather than in

time) in order to facilitate the comparison with experimental data

which are taken along the spatial extend of the flume. Consistent

with the wave generator located at \(x=0\), we specify

\(\psi(x=0,t)=\psi_0(t)\) as initial condition for the NLSE, which we

take to be a Gaussian random field with a covariance whose Fourier

transform is related to the JONSWAP spectrum.

Large Deviation Theory and Instanton Calculus

Our analytical and computational descriptions of rare events rely on

instanton theory. Developed originally in the context of quantum

field theory, at its core lies the realization that the evolution of

any stochastic system, be it quantum and classical, reduces to a

well-defined (semi-classical) limit in the presence of a small

parameter. Concretely, the simultaneous evaluation of all possible

realizations of the system subject to a given constraint results in a

(classical or path-) integral whose integrand contains an action

functional \(S(\psi)\). The dominating realization can then be obtained

by approximating the integral by its saddle point approximation,

using the solution to \(\delta S(\psi^*)/\delta \psi=0\). This critical

point \(\psi^*\) of the action functional is called the instanton, and

it yields the maximum likelihood realization of the event. This

conclusion can also be justified mathematically within Large Deviation

Theory.

Specifically, we are interested in the probability

$$

P_L(z) \equiv \mathbb{P}(\eta(L,0)\ge z)

$$

i.e. the probability of the surface elevation at position \(L\) at an

arbitrary time \(t=0\) exceeding a threshold \(z\). This probability can

in principle be obtained by integrating the distribution of the

initial conditions over the set

$$

\Lambda(z)=\{\psi_0: \eta(L,0))\ge z\},\label{eq:13}

$$

i.e. the set of all initial conditions \(\psi_0\) at the wave maker

\(x=0\) that exceed the threshold \(z\) further down the flume at

\(x=L\). Since the initial field \(\psi_0(t)\) is Gaussian, the probability \(P_L(z)\) can therefore be

formally written as the path integral

$$

P_L(z) = Z^{-1} \int_{\Lambda(z)} \exp(-\tfrac12 \|\psi_0\|^2_C)\,D[\psi_0]\,,

$$

where \(Z\) is a normalization constant and the \(C\)-norm is induced by

the energy spectrum (in this case, JONSWAP) of the initial condition.

The set

\(\Lambda(z)\) has a very complicated shape in

general, that depends non-trivially on the nonlinear dynamics

of the NLSE since it involves the field at \(x=L>0\) down the

flume rather than \(x=0\). One way around this difficulty is to

estimate the integral via Laplace's

method. This strategy is the essence of Large deviation theory

(LDT), or, equivalently, instanton calculus, and it is

justified for large \(z\), when the probability of the set \(\Lambda(z)\)

is dominated by a single \(\psi_0\) contributing most to the integral. The optimal

condition leads to the constrained minimization problem

$$

\tfrac12\min_{\psi_0\in \Lambda(z)}\, \| \psi_0\|^2_C\equiv I_L(z)\,,

$$

and gives the large deviation estimate for \(P_L(z)\) of,

$$ P_L(z) \asymp \exp\left(-I_L (z) \right)\,,$$

where the symbol \(\asymp\) means asymptotic logarithmic equivalence,

i.e. the ratio of the logarithms of the two sides tends to 1 as

\(z\to\infty\), or, in other words, the exponential portion of both

sides scales in the same way with \(z\). Intuitively, this

estimate says that, in the limit of extremely strong (and

unlikely) waves, their probability is dominated by their least

unlikely realization, the instanton.

Now, the stochastic sampling problem is replaced by a deterministic

optimization problem, which we solve numerically. The trajectory

initiated from the minimizer \(\psi_0^*\) of the action will be referred

to as the instanton trajectory, and in the following we compare it

to trajectories obtained from the experiment.

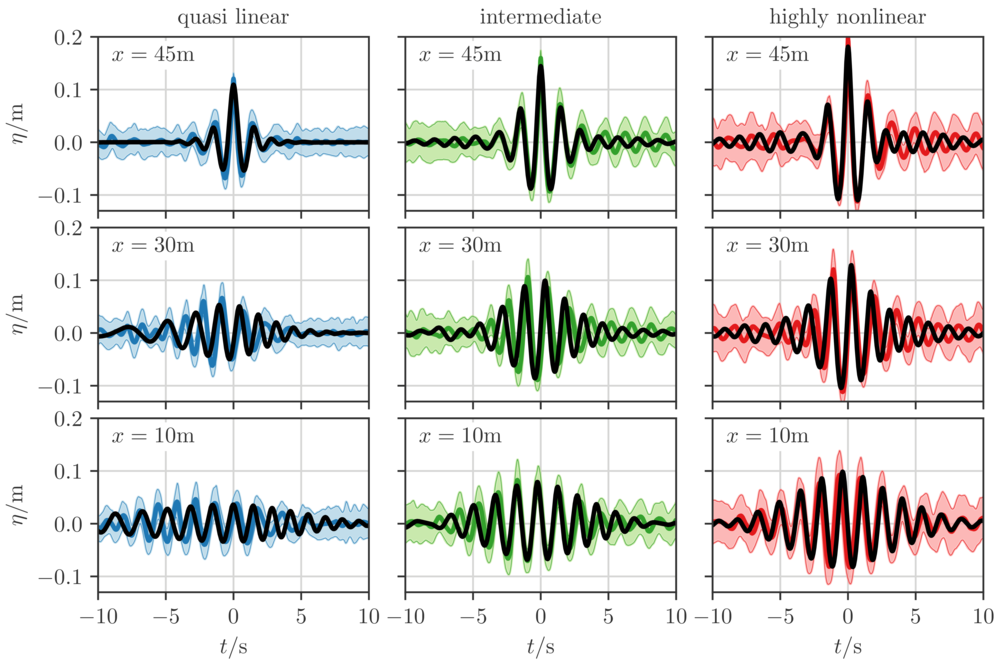

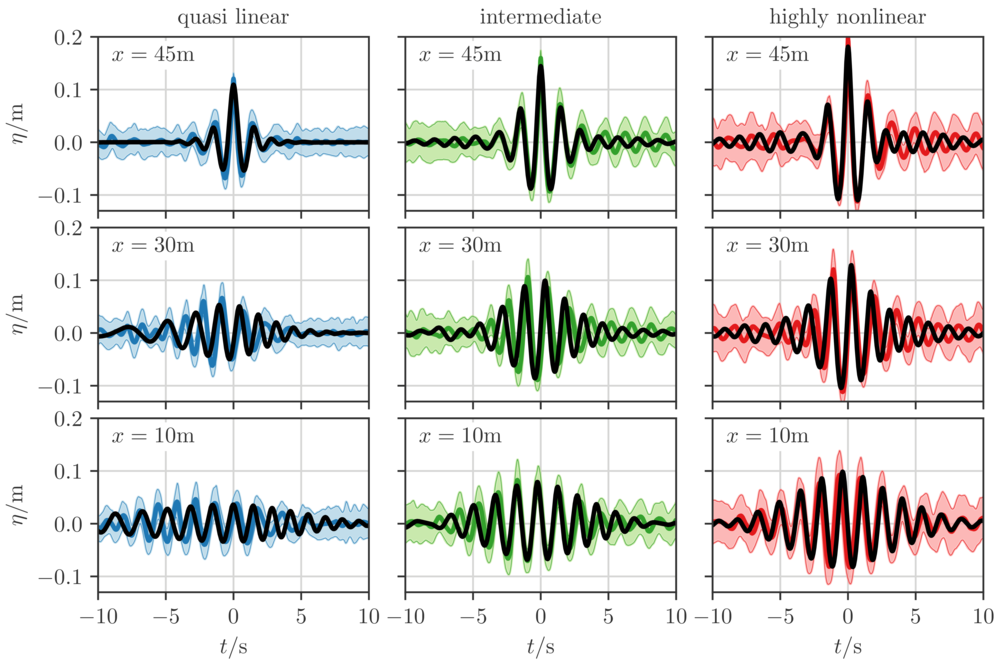

Experimental Rogue Waves compared to Instantons

In the figure above, numerically computed instanton realizations are

depicted in solid black, while experimental averages and their

standard deviation are in color. We compare the evolution of rogue

waves observed in the experiment and averaged over many realizations

to that of the instanton, both constrained at \(x=45\) m. In all cases

the instanton tracks the dynamics of the averaged wave very closely

during the whole evolution. Moreover, in the focusing region the

standard deviation around the mean is small, especially toward the end

of the evolution. This observation in itself is a statement that

indeed all of the rogue waves such that \(\eta(L,0)\ge z\) resemble the

instanton plus small random fluctuations. The instanton approximation

shows excellent agreement not only across different degrees of

nonlinearity (and therefore substantially different physical

mechanisms), but also captures the behavior of precursors earlier

along the channel.

It is worth stressing that the instanton approach captures both the

linear and the fully nonlinear cases, unlike previous theories that

could describe each of these regimes individually but not both. To

make that point, in the next two sections we compare the predictions of

our approach to those of the quasi-determinism and semi-classical

theories that hold in the dispersive and nonlinear regimes,

respectively.

Conclusion

Here we have proposed a unifying framework based on Large Deviation

Theory and Instanton Calculus that is capable to describe with the

same accuracy the shape of rogue waves that result either from a

linear superposition or a nonlinear focusing mechanism. In the limit

of large nonlinearity, the instantons closely resemble the Peregrine

soliton to describe extreme events, but with the added bonus that our

framework predicts their likelihood; in the limit of linear waves, the

instanton reduces to the autocorrelation function. A smooth transition

between the two limiting regimes is also observed, and these

predictions are fully supported by experiments performed in a large

wave tank with different degrees of nonlinearity. These results were

obtained for one dimensional propagation, but there are no obstacles

to apply the approach to two horizontal dimensions, which may finally

explain the origin and shape of rogue waves in different setups,

including the ocean.

Relevant publications

-

G. Dematteis, T. Grafke, M. Onorato, and E. Vanden-Eijnden,

"Experimental Evidence of Hydrodynamic Instantons: The Universal Route to Rogue Waves",

Phys. Rev. X 9 (2019), 041057

-

G. Dematteis, T. Grafke, and E. Vanden-Eijnden,

"Extreme event quantification in dynamical systems with random components",

J. Uncertainty Quantification 7 (2019), 1029

-

G. Dematteis, T. Grafke, and E. Vanden-Eijnden,

"Rogue Waves and Large Deviations in Deep Sea",

PNAS 115 (2018), 855-860

-

T. Grafke, R. Grauer, and T. Schäfer, "The Instanton Method and

its Numerical Implementation in Fluid

Mechanics",

J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 48 (2015), 333001